Marcel Ophuls' 'The Sorrow and the Pity' Changed Theatrical Documentary History

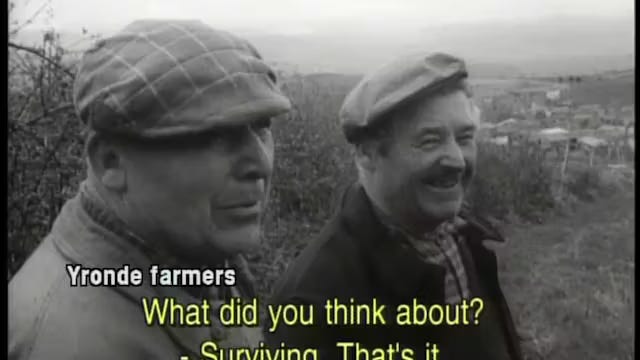

‘The Sorrow and the Pity’

Marcel Ophuls’ death at 97 over the weekend brought attention to the great documentarian’s career, with appropriately the focus on the substance and quality of his work. Key films, starting with “The Sorrow and the Pity,” then later including “A Sense of Loss,” “Memory of Justice,” and “Hotel Terminus,” were central to elevating non-fiction film over a two decade period in the 1970s and 1980s.

Though the success of “Sorrow” has been noted in most obituaries, less discussed has been its transformational role in pushing the boundaries of theatrical documentary distributed films. Its succesful play, particularly in the U.S., in 1972 and 1973 had a profound impact on what was considered commercial viable for nonfiction film.

Ophuls, the son of Max Ophuels (the brilliant German director who later made masterpieces in Hollywood and France) had a minor career in feature films in the 1960s. He made one of the segments in “Love at 20” (best known for Francois Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel entry) and a comedy with Jean-Paul Belmondo (“Banana Peel”) before transitioning to French television documentaries.

“Sorrow” was originally produced for French television. That helps explain its 4.5 hour length (it was intended to be shown in two parts there). And it also made sense to be presented for the small screen - for the initial decades of television, documentaries about history and contemporary events were a staple of programming. In the U.S., CBS in particular had prime time series like “See It Now,” “The 20th Century,” and “CBS Reports.”

Documentaries of course always had a foothold in theatrical distribution. Apart from newsreels as part of programming packages, big cities had theaters dedicated solely to them. Films about explorers and remote peoples attracted top filmmakers like Robert Flaherty and F.W. Murnau. When Cinerama presentation entered in the early 1950s, many of their films (massive hits) were travelogues. Parallel to this were exploitation films (“Reefer Madness”) that challenged censorship and promised seaminess that studio films couldn’t touch. The 1960s saw a series of pop music documentaries (“Monterey Pop,” “The T.A.M.I. Show,” “Don’t Look Now,”) with “Woodstock” in 1970 grossed in 2025 terms over $400 million.

But absent from screens to any significant extent, even among specialized theaters, were contemporary issue documentaries. Even at the height of the Vietnam war (made immediate by tv news coverage), a handful of films about it (“The Anderson Platoon,” “A Face of War,” “In the Year of the Pig”) did minimal business.

“The Sorrow and the Pity,” played to great acclaim at the New York Film Festival in 1971 (it was completed in 1969, shown initially then on West German TV, with Paris theatrical runs initially in July 1971). U.S. rights were acquired by Cinema 5 Films, owned by New York’s then leading specialized exhibitor Don Rugoff.

That to a large extent was its secret sauce beyond its compelling success. The initially scrappy independent distributor’s first big success was the surfing documentary “The Endless Summer” (1966), which grossed over $5 million ($50 million today).

Consistent with what played at Cinema 5’s Manhattan theaters and dominated specialized theaters then, most of their films were non-English. They also continued to elevate documentaries - “Gimme Shelter” (1970), “The Hellstrom Chronicle” and “On Any Sunday” (1971), “Marjoe” (also in 1972).

Cinema 5 gave a film a significant imprimitur as well as the critical element of a major New York opening. But a 4.5 hour documentary about one occupied French city during World War 2, upending decades of myth about local resistance? That was radical.

The film opened (apart from an awards’ qualifying run) opened limited on March 25, 1972, at the end of the voting period for the 1971 Oscars. The date eemed aimed to capitalize on the nomination and hoped-for win.

Though it didn’t win (the faux gimmick insect world “Hellstrom” did in one of the most egregious Oscar mistakes; Ophuls later won for “Hotel Terminus”), backed by strong reviews it did decent enough business to gain a foothold and attract further bookings. It was presented as one program (single ticket), with its length not only making it a viewing challenge but also obviously limiting showtimes and available seats.

Though no official figures seem available, it looks like it grossed, again adjusted to current ticket prices, as much as $4 million. (Variety, which tracked a sampling of theaters but not all showed it at $406,000 in early October; I saw it in suburban Chicago in January 1973, where it played an unusually long three week run). That was a decent total for a specialized release at the time, more so for a subtitled one. For a French documentary on a serious subject over four hours? Unheard of.

Both the New York Film Critics (for the first time in its 37 year history) and the more recently formed National Society of Film Critics gave it a special award (neither group gave an annual prize in the category until the 1980s, which by itself says something about how seriously theatrical ones were taken up to then). Its further cultural status as seen when Woody Allen included it as a plot element in “Annie Hall.”

It takes a while for patterns to adapt, but within two years, its success bore fruit. “Hearts and Minds,” the later-Oscar winning Vietnam documentary, premiered at Cannes 1974. Though original distributor Columbia rejected the film, Warner Bros. (!) released it theatrically, giving it significant nationwide exposure.

By 1975, documentaries were more common theatrically: “Grey Gardens,” “The Man Who Skied Down Everest,” “Harlan County U.S.A.,” “Pumping Iron,” “From Mao to Mozart",” “Best Boy” among those getting real attention the rest of the decade. That was a vastly changed landscape than before “Sorrow.” PBS and other broadcasters got more creative in their productions (“Scared Straight” as one key example).

“Hearts and Minds” in particular (hard to imagine any studio backing it without the example of “Sorrow”) was cited by Michael Moore, the most successful political documentary director since, as what got him interested in the field. Ken Burns, the leading historical documentary creator, has made a career (abetted by TV flexibility) in making monumental length films. It’s easyt see how the non-traditional length of “Sorrow” made this easier. Claude Lanzmann’s equally 1985 epic “Shoah” (566 minutes), also originally produced for TV but getting theatrically play in the U.S. (though as a special not conventional presentation), though much different in style and content, also came in its wake.

“The Sorrow and the Pity” is a masterpiece that even without this influence would stand as one of the greatest non-fiction films. But it deserves additional attention for how it changed documentary theatrical distribution history.

It can be rented for 48 hours from several platforms for $3.99, with the Blu-Ray available from Milestone Films.

(For more on Cinema 5 films, see Ira Deutchman’s excellent documentary “Searching for Mr. Rugoff,” streaming on the Criterion Channel, and also on VOD platforms).

That was a great tribute to both a great film and a great artist. Thanks for writing it!