Ted Pedas (1931-2025)

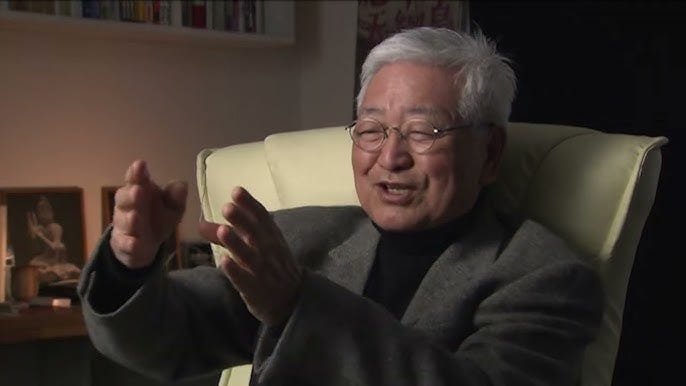

Masahiro Shinoda (1931-2025)

Two major figures in the film world, one from exhibition (with a significant production sideline) and one major Japanese director, both born in 1931, died in the last week. It appears neither has been mentioned by any of the major American entertainment media outlets, nor by major newspapers like the New York Times or the Guardian (in the case of directors) who usually make note of significant deaths.

For a full obituary for Ted Pedas, the leading Washington D.C. specialized exhibitor in the 1970s and 1980s, read this in the Washington Post or this tribute by Ira Deutchman, a top specialized distributor (Cinecom, Fine Line) during this period of later. Pedas died on March 21 at 93.

Masahiro Shinoda, a central figure in the Japanese New Wave of directors from the 1960s (Nagisa Oshima and Shohei Imamura the best known in the West), died on March 25, a couple months older at 94. The Tinseltown Twins published this fine overview yesterday.

Ted Pedas was one of the last survivors of a class of specialized theater operator that was once dominant in major U.S. cities. Localized, coming out of other career trajectories (in his case, law; real estate is another background source), he and his brother Jim, after initially operating some drive in theaters in the 1950s, took hold of a long-standing D.C. theater (the Circle) in the 1960s, and turned it into a thriving repertory theater (showing classic films, not uncommon in the era).

That led to expanding into first-run specialized locations, centered around the Circle and the Inner Circle, which though not without competitors became the leading Washington art houses by the late 1970s then into the key boom period of the 1980s.

Circle, and Pedas, became the go-to place for top distributors in the city. This was not unusual, with local operators becoming dominant in Boston (Sack, later USA theaters, run by Alan Friedberg, later CEO of Loews), Philadelphia a bit later (Ray Posel’s Ritz Theaters), Jon Forman in Cleveland (still operating), George Lafont in Atlanta, Oscar Brotman and then M & R Theaters in Chicago (I was film buyer for both). Not being in the biggest cities, they never were as well known as New York’s Don Rugoff/Cinema V, and Dan Talbot, and Ben Barenholz, or the Laemmles in Los Angeles. The west coast also had Mel Novikoff, Ray Price, Gary Meyer, and others in San Francisco, Randy Finley, Bert Manzari, and Dan Ireland out of Seattle (some of these better known in repertory more than repertory specialized early on).

That’s a world of change from today when the top runs of specialized films outside of some Manhattan locations come from AMC and other top chains, Alamo Drafthouse and to a much lesser extent Landmark Theatres, ahead of independently owned ones in top cities.

Ted Pedas was an exemplar of an owner who had taste, finesse, business sense, and passion, and combined these to build a reputation that elevated his local theaters to central to the cultural life of his city.

This was an era when, as Philadelphia Inquirer film critic Carrie Rickey wrote in Ray Posel’s obituary in 2005 about his Ritz Theaters, “They have become as irreplaceable a Philadelphia cultural institution as the Museum of Art.” (One of the top honors of my career as a film buyer was to be chosen to program his theaters after his death).

Those of us lucky enough to have been part of this scene in the 1980s and following can relate to how it felt like a privilege to work in this field, over and above regular exhibition. It brought a special degree of respect. M & R in Chicago was the leading local chain at that time. Co-owner and my mentor Richard Rosenfield told me when he met with real estate developers, that we operated the Fine Arts (profitable, but not as much as our top general theaters) that it immediately elevated our company in their eyes.

Back then, local operators like Pedas were central to any specialized success. None survived by being anything but tough negotiators, and fiercely protective of their turfs. I didn’t know Ted as well as some of the others (I did have regular contract with his film buyers to compare notes), but among our group he had the reputation as having a patrician aura above the more rumble/tumble and sometimes rougher edged characteristics of our peers.

By the late 1980s, prompted by aggresive moves by Toronto’s Garth Drabinsky and Cineplex Odeon (itself with roots in specialized), a wave of acquisitions started that swept up most of these theaters. Their distinctiveness - the local roots, the sense of nuance, and promoting to a loyal group of customers - has diminished.

But it is returning to some degree, with locally based theaters flourishing in Chicago (the Music Box), the Boston area (Coolidge Corner), Nashville (the Belcourt) to cite just three. Ted’s spirit lives on in these types of situations, though replicating as much power or exclusivity initially as his theaters did is hard to imagine today.

If other industry articles are written about him, they likely will center on his company’s involvement with the early films from the Coen Brothers. Circle Films, which they started in the early 1980s, acquired their first film “Blood Simple,” then in assocation with partner Ben Barenholz had a significant production role in their immediately following films. That is noteworthy.

But his legacy should be his role as a specialized exhibitor. He was at the top of his field. Ira’s tribute linked above includes an outtake of his interview with him, and more footage is in his excellent documentary “Searching for Mr. Rugoff” available on Criterion or Prime.

Not to diminish Shinoda’s importance in comparison by sharing this space, I just thought it was important to alert people familiar with his work to his death since the news has been absent from the usual places as well as introduce it to others. Such is the fate of major non-American filmmakers who didn’t break through in American theaters (only a handful of his films, led by “Gonza the Spearman” and “MacArthur’s Children,” saw contemporary distribution beyond festival play). Most significantly perhaps, his 1971 “Silence” was remade by Martin Scorsese.

With the significant help of the Criterion Collection, which showcases much of his work, I’ve seen around 20 of his 32 features. Unlike Akira Kurosawa, by far the best known Japanese director (but also far more Westernized than most others; I admire much of his work but regard Ozu, for whom Shinoda was an assistant, Mizoguchi, Ozu, and Kinoshita from the classic era as superior), Shinoda is less accessible to American cinephile tastes. But he was a major artist and his death worth more attention along with his films.

The current (Spring) issue of Cineaste has a feature about Shinoda.

I would add Chicago's Larry Edwards (Biograph) to your specialized honor roll. The common thread was that all of these owners had such good taste and key venues s highly sought by specialty distrubution that any title they booked opened with the implied benefit of importance.